In this month’s Investment Strategy Note we review the Fed’s last nine hiking cycles to assess the likelihood of a soft landing during this cycle.

If you believe financial markets, the U.S. Federal Reserve has finished hiking rates this cycle.

The rate rise cycle started back in March 2022 when, to combat the highest inflation in the U.S. in four decades, the Fed rapidly raised its Federal Funds Rate from 0.25%, reaching 5.50% by July this year.

With growth in inflation now receding, the market – based on its pricing at the time of writing – sees the Fed pausing from July this year through until March 2024, when it predicts the Fed will start cutting rates.

The key question on every investor’s lips is: what does this mean for share markets?

Ultimately, what happens to the S&P500 – the key barometer and driver of global share markets – depends largely on whether the U.S. economy enters recession after the pause in rates.

At the moment, the ‘goldilocks’ combination of weakening inflation and reasonable economic growth suggests the probability of the Fed having engineered a soft landing (no recession) has increased.

But based on Bloomberg’s survey, economists are still forecasting about a 50% chance of recession in the U.S. over the next year, so there is still clearly some risk remaining for the S&P 500.

Below, we look at why a ‘soft landing’ is so hard for the Fed to stick.

And to gauge the likelihood of a soft landing during this cycle, we look closely at how often the Fed has managed to make a soft landing when its last nine hiking cycles ended.

Was the 1995 hiking cycle the only one where the Fed got the water just right?

The common view is that the Fed has only managed to pull off one soft landing in its history. That was the rate-hiking cycle that began in February 1994 and ended in February 1995 (referred to as ‘1995’ in chart below).

This elusive ‘soft landing’ helped propel then Fed Chairman, Alan Greenspan, into the history books of famed central bankers. (Of course, his reputation was tarnished by his overly loose monetary and supervisory policy that contributed to the GFC.)

Why are soft landings so rare?

Another famed economist, Milton Friedman, highlighted the “long and variable lags” between changes in monetary policy (interest rates) and its impacts on the economy.

Friedman’s ‘Fool in the Shower’ analogy highlights the practical challenges.

You may jump in the shower and turn on the hot water tap (change interest rates) but feel nothing but cold water. So, you keep turning the hot water tap up and up (keep moving rates in one direction).

But it takes a long time for the water to come through the pipes. So when it does arrive it is scoldingly hot, and you find you’ve gone too far (taken rates too far – either overstimulating on one hand or crashing the economy on the other).

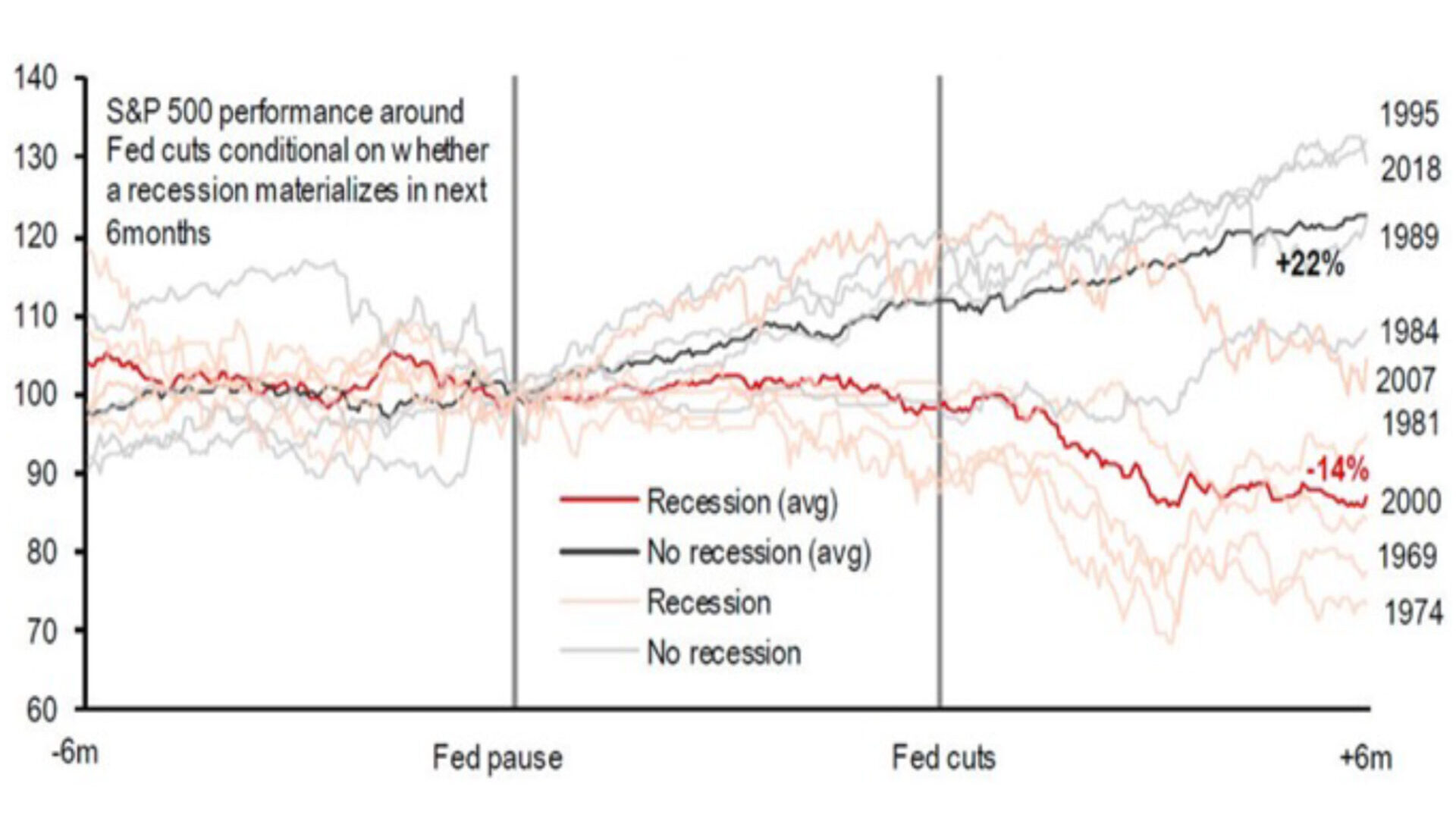

Performance of S&P 500 around FED pauses and easing

Source: FTSE Russell, Factset, HSBC

The chart above from strategists at HSBC, however, suggests there may be some other soft landings in addition to 1995 hiking cycle including the 1984, 1989 and 2018 hiking cycles.

That’s much more than many would suspect, which if true, may raise the hopes the Fed can stick the landing again this cycle.

What happened to the economy and share markets in the past nine hiking cycles?

So are soft landings common or not?

Below, we put together a table that collates the size of rate hikes for the Fed’s past nine cycles, the length of the pause, the size of any subsequent recession, and how much the S&P500 fell.

Source: Bloomberg, Ophir.

But which ‘no recession’ soft landings should be counted in the Fed’s favour when determining their credibility for sticking another?

To find out, let’s look at each cycle in turn.

1969 (Recession): This was a very soft fall in GDP, but unemployment rose 2.4% which is not so soft! Both fiscal and monetary policy were restrictive in this episode. It was one of the rare times when fiscal policy pitched in to slow demand and inflation. The small contraction in GDP might prompt one to call this a soft landing, and Treasury helping with restrictive policy might incline some to give the Fed a free pass here. But the unemployment rate increase and the size of the S&P 500 fall suggest it does indeed belong in the recession camp.

1974 (Recession): Inflation rocketed because of President Nixon’s August 1971 wage and price controls, Fed Chair Burns’s monetary stimulus (with encouragement from Nixon), and supply side oil price shocks. Annual core inflation increased from 3.3% in Feb 1972 to 8.8% just five months later. An inflationary recession unfolded with stagflation becoming well entrenched. This was the biggest economic downturn since the Great Depression at the time. With no clear playbook on how to deal with supply side inflation shocks back then, this was a hard landing.

1981 (Recession): The ‘OPEC 2’ crisis hit the world economy and oil prices skyrocketed as Iraq invaded Iran. Paul Volcker took over from Arthur Burns as Fed Chair (after a very brief interlude by Will Miller as Fed Chair in 1978/79). While Burns and Miller had started raising rates, Volcker went much further, taking rates to 20%. Volcker was happy to accept a hard landing as the price for getting inflation under control. That was certainly what he got, with a long recession and big 3.6% increase in unemployment.

1984 (No Recession): People still debate whether this was really a tightening cycle, or just a return to ‘normal’ rates from abnormal lows following the early 80s recession. This was the start of what many now call the Great Moderation. This was as soft a landing as you could get, with the unemployment rate trending down during the whole hiking cycle. It’s hard to compare this episode to today’s given the Fed is fighting an inflation war this time, not just normalising rates.

1989 (No immediate recession but one did follow in 1990): This could easily be called a recession because one did ensue in July 1990. It just took some time after the rate cutting cycle started. The recession ultimately lasted for eight months and GDP fell -1.4%. The unemployment rate rose 1.3% during the recession and the S&P500 posted a -19.9% drawdown in 1990. Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait in the second half of 1990 didn’t help, with the oil price more than doubling and recession ensuing. Would a recession have been avoided but for the oil price spike? We’ll never know. The analogy to today would be a left field event causing recession in 2024, robbing us of ever knowing whether the Fed’s hiking cycle would have performed a coup de grace on the U.S. economy.

1995 (No Recession): This soft landing is the one called out by almost everyone and is the one that made Greenspan a feted legend – at least at the time. No recession, no increase in unemployment and inflation remained low and stable. A key difference here was that the Fed was not trying to crush inflation, but instead trying to get the ‘real’ (after inflation) Fed policy rate into more normal positive territory. Today it is trying to crush inflation.

2000 (Recession): This cycle saw the smallest amount of tightening and produced a very modest recession. Unemployment ticked up, but just 1.2%. It was the stock market crash, particularly in tech stocks from the popping of the Dot.com bubble, that helped push the economy into recession. A small recession, but recession nonetheless, and share market investors certainly felt the pain.

2007 (Recession): The Fed hiked rates by 4.25% over two years from June 2004 to June 2006. Before this, in hindsight rates were too low for too long. That helped cause the housing bubble that led to the housing market and the banking sector’s subsequent collapse during the GFC. But did the hiking cycle cause the hard landing? Partly. But lax regulatory and supervisory policies across the banking and housing sectors played a major role.

2018 (No Recession from rate hikes, but COVID did ultimately cause one): This tightening in rates occurred over a very long period, from late 2015 to late 2018. It was gentle tightening of just 2.25% of cumulative rate increases, and more a normalisation from ultra-low 0% rates during the GFC. Covid was ultimately the cause of a very short and sharp recession that lasted just two months, but U.S. GDP fell an incredible -19.2% as large swaths of the economy were shut down. Would a recession have occurred anyway if not for COVID? The yield curve did invert (a harbinger of recession) before COVID struck, but ultimately, we’ll never know.

Soft landings are more probable than we think

In summary, the last 60 or so years of history suggest the Fed’s rate hiking cycles more often than not end in recession … and that is bad for share markets. The chart and table above make this clear with 25-50% market falls typically seen if a recession ensues.

And as we’ve seen, ‘other factors’ outside the Fed’s rate hikes often also contribute to, or cause, the subsequent recession (for example, contractionary fiscal policy in ’69; the oil price spike which contributed to the ’90 recession; the Dot.com bubble bursting for the ’00 recession; and lax regulatory policy contributing to the GFC).

Many soft landings, such as in ’84 and ’95, were also more about returning policy to what was viewed as more ‘normal’ levels at the time, rather than fighting an inflation battle, so are perhaps less relevant to today’s inflation fight.

But soft, or softish landings, happen more than many may think – certainly more than once in the past nine cycles – with better outcomes for investors.

The bottom line here is historically recessions happen more often than not at the end of hiking cycles, whether the Fed causes it or something else helps tip the economy over the edge. Many of the soft landings but not all, have been about returning policy to normal levels, not fighting an inflation battle like the Fed is today. There is some hope for a soft landing but historically it has not been the base case.

Recession risk elevated but receding – how to position?

So what do we think is likely to happen?

Will the Fed’s hikes cause recession and trigger possibly big falls on the S&P500?

Will something else, encouraged by rate hikes, cause recession, or even a left field event that causes it?

Or will the rare – but possible – soft landing be achieved? No doubt vaulting Chair Powell to legend status.

We believe recession risk in the U.S. still remains high. Inflation has fallen more than expected though whilst the economy has still hung in there longer than many, including us, expected. The reasons for this resilience are now better understood (COVID excess stimulus and slow transmission of rate hikes) but we also see slowing in the economy at the coalface from companies revenue and earnings guidance.

We remain positioned in the Ophir Funds with larger allocations to companies with more resilient and less macroeconomically sensitive earnings. We do hold companies with more cyclically driven business models, but they tend to be smaller positions. We expect at some point in the next year their time will come for larger weights in our portfolios when a more durable and broad market recovery arrives.