In our Investment Strategy Note we discuss what higher bond yields might mean for equity returns.

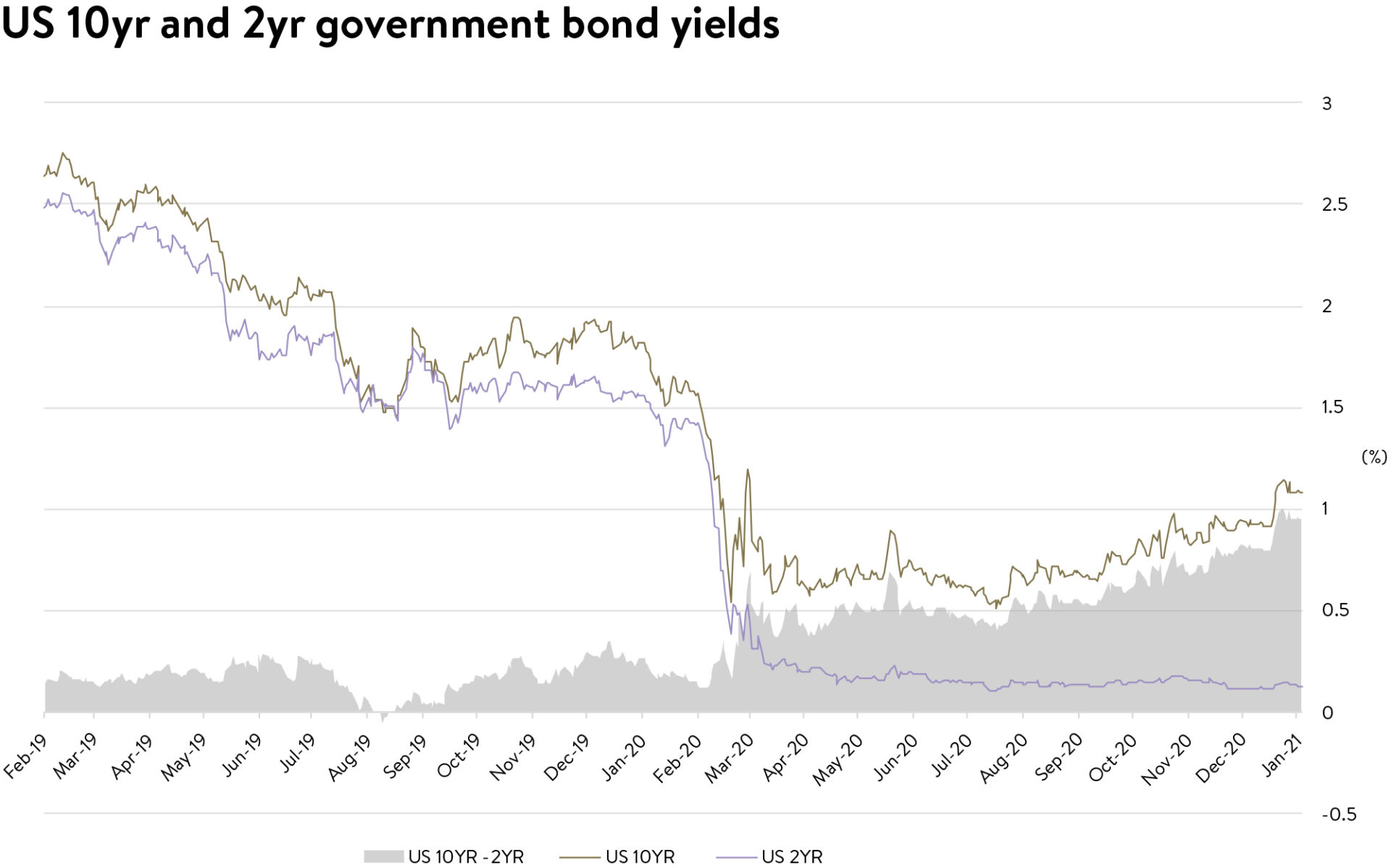

Investors have been focused on the bond market in recent weeks because they have seen something unfamiliar – rising bond yields. In the first week of January, the US government 10-year bond yield (the rate of interest the US government borrows at) surpassed the psychological barrier of 1% for the first time since the Covid shock began.

US 10yr and 2yr government bond yields

Source: Bloomberg

Given lower bond yields have been used to justify higher share market valuations for much of the last decade, rising yields could pose a threat to equities.

Some seasoned and sceptical investors have been arguing for years that equity valuations have become dangerously dependent on the persistence of historically low bond yields.

While we don’t believe the rise in bond yields is dangerous yet, or reflects the threat of a sharp acceleration in inflation, rising yields will likely be a headwind in gains for equities. And that means that if investors want to generate strong returns from equities in coming years, they will need to focus on stock picking skills.

Why bond yields have been heading higher

Expectations around economic growth and inflation have driven bond yields higher. The emergence of effective coronavirus vaccines has triggered optimism that the global economy will rebound powerfully in 2021. The US Senate elections in Georgia, which handed Democrats control, has also increased the Democrat’s ability to drive through a reflationary economic agenda. Yet even as the pandemic recedes, it appears central banks are set to maintain policy rates at or near zero, further allowing inflation pressures to build. This comes as the US Fed, as well as the Australian RBA, want to now wait longer to see actual inflation heading sustainably higher, rather than expected inflation, before they start lifting interest rates.

How bond yields affect equity valuations

Bond yields are an important determinant of equity valuations. When bond yields go down, share market valuations tend to rise … and as bond yields go up, share markets tend to falter.

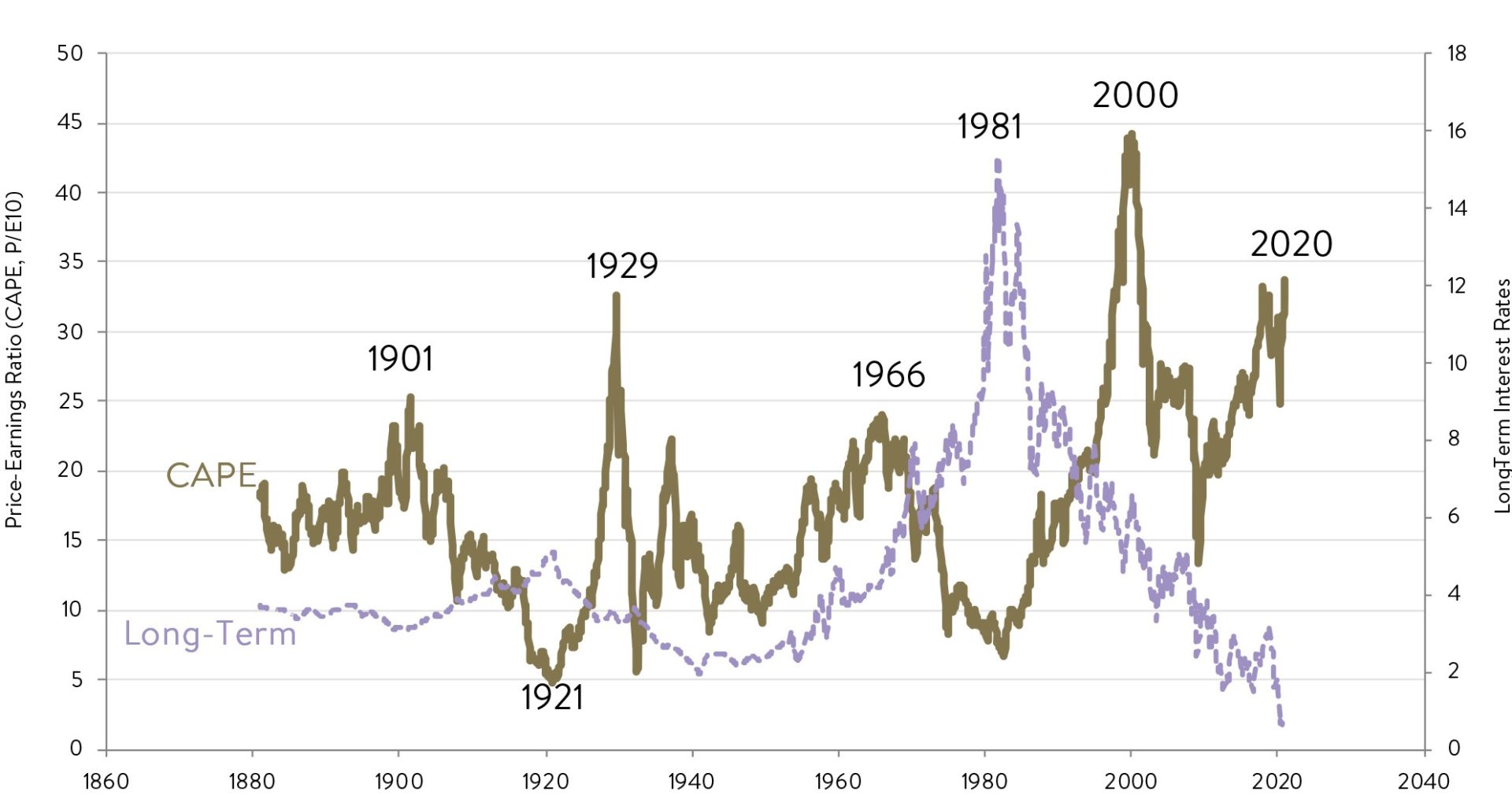

The relationship may not exactly hold in the very short-run, but it becomes more clearly visible over longer time periods as can be seen in the figure below (cyclically-adjusted price-to-earnings ratio used as a share market valuation measure).

US Equity Market Valuation vs Bond Yields

Source: Shiller data, Yale

There are three key and interrelated factors that link bond yields with equity valuations:

- Firstly, bond yields drive the opportunity cost of equities. If, for example, the 10-year bond is yielding 5% per annum, then equities only become attractive if they can earn well above 5%. In fact, because equities are riskier than bonds, investors will demand a ‘risk premium’ to justify owning them. The long-term average risk premium on equities is 5%. So a 10% return – the 5% investors could get from bonds + the 5% risk premium — will act as the opportunity cost for equity. Below a 10% return, it makes less sense for investors to hold equities because they are not being compensated for the additional risk. So as bond yields go up, the opportunity cost of investing in equities also goes up, and equities become less attractive.

- Secondly, bond yields also impact the cost of capital in valuing equities. The yield on bonds is typically used as the risk-free rate when calculating this cost of capital. When bond yields go up, the cost of capital goes up. That means that future cash flows get discounted at a higher rate, meaning a $1 of cash flow received in the future from a company is worth less today. This compresses the valuations of these stocks.

- Thirdly, bond yields impact financial costs for companies. When bond yields go up, it is a signal that corporates will have to pay a higher interest cost on debt. As debt servicing costs go higher, the risk of bankruptcy and default also increases, typically making highly leveraged companies vulnerable.

Good and bad market volatility

Although bond yields do impact share valuations, investors should be more worried about losses that result from a downward revision of a company’s earnings potential, than losses caused by an increase in interest rates (all else equal).

The former suggests a market assessment that there is now a greater chance that the business will fail to deliver its expected earnings growth. While losses from increasing rates indicates the adjustment of the rate of discount, without a revision of market views on the company itself.

Indeed, to achieve long-term success, investors should distinguish between good and bad volatility. This is particularly invaluable for private investors who often regard any loss as bad news, when it may be an opportunity to lock in access to higher future income. For example, a move up in bond yields allows investors to buy and lock in future income at a lower cost. That’s good news for anyone saving for a pension or an education endowment. For superannuation savings plans, it means that more future pension income can be bought with each new dollar of savings.

Should investors be worried?

The critical question is whether the current move up in bond yields goes beyond a healthy reflation that reflects the post-pandemic economy, and surges into inflation.

Presently markets are positioned for the former: that is, the economy will recover, but inflation will stay under control, and interest rates will remain low.

Even under this scenario, investors should still factor in that equity valuations are likely to be pressured over coming years as interest rates trend higher. This means that strong equity returns will have to rely more on actively selecting the stocks that can generate sustainable earnings growth, and less on free kicks from falling bond yields and central banks cutting interest rates.

Or in other words, a greater proportion of returns are likely to come from stock picking skill rather than a rising tide lifting all boats (read: companies) in the market.