In our Investment Strategy Note we review some of the personal foibles that could be sabotaging your investing and offer some solutions to make sure your cognitive shortcuts aren’t leaving you short changed.

Warren Buffett’s teacher at Columbia University, and famed value investor, Ben Graham, is famous for saying: “The investor’s chief problem – and even his worst enemy – is likely to be himself.”

From experience, we know this is true. If you cannot control your emotions and face up to your foibles, the sharemarket can be an expensive place to find out.

How you behave when investing, often has a bigger influence than your investing knowledge. This is more relevant than ever given the abundance of information that’s out there nowdays prompting investment action, combined with a dramatic increasing in the ease at which investors can trade.

If investors can better understand their investing psychology – particularly four big cognitive biases we look at below – they will be less likely to make mistakes, such as selling too soon and holding onto losing stocks, because of poor unconscious thinking. But they will also be better placed to exploit the mistakes of other investors, including picking up undervalued stocks, and gain a massive competitive edge in building their wealth.

Rational or normal?

At times, investors lack self-discipline, behave irrationally, and decide what to invest in based more on emotions than facts. The study of these influences on investors and markets has come to be known as behavioural finance. Traditional theory says markets and investors are rational; behavioural finance believes we act as humans. Or as another giant in the field of finance, Santa Clara University economist, Statman, puts it: “People in standard finance are rational. People in behavioural finance are normal.”

Behavioural finance uses research from psychology that describes how individuals behave and applies those insights to finance. Recognition of the contribution that behavioural finance has on financial economics was reflected in 2002 with the Nobel Prize in economics being awarded to Professor of psychology, Daniel Kahneman, who you may recognise from his popular book Thinking, Fast and Slow.

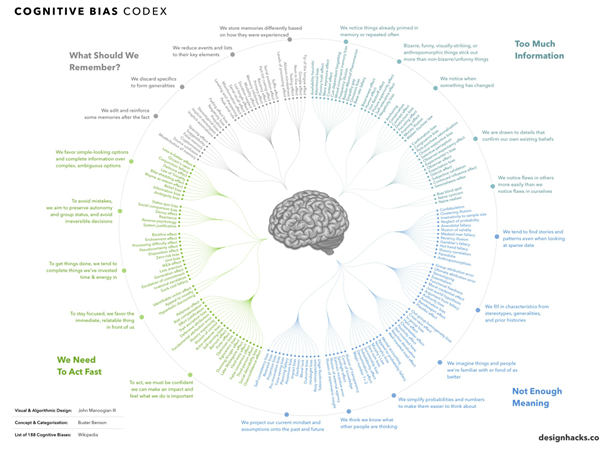

The umbrella of knowledge under behavioural finance continues to grow and evolve. As you can see in the chart below, there are over 180 cognitive biases that have been discovered to date.

But we believe that portfolio managers, and investors in general, need a firm grasp of four key biases to understand how other investors may respond to particular events or market developments.

1. Overconfidence (buying too high and trading too much)

The overconfidence bias is when we delude ourselves that we are better than we really are.

Surveys routinely show that more than 80% of people think they are better than average for a whole list of things, including driving, intelligence … and even looks. Heck, 84% of the French believe they are above average lovers!

In investing, overconfidence can lead you to believe that you know more about a stock or the market than you do. Various studies have tested the effect of overconfidence bias in financial markets. In one study, Bloomsfield (1999) found that overconfident behaviour unconsciously increases investors’ propensity to buy stocks too expensive or sell stocks that are too cheap. Overconfident investors also tend to trade stocks more often than they should and underestimate downside risks. In these instances, when it comes to accumulating wealth overconfidence is detrimental.

Solution: At Ophir, we try to fight overconfidence by stress testing all our stock ideas in a team environment where everyone else acts as devil’s advocate. We also explicitly consider how the stock would perform in a GFC-style scenario.

2. Loss Aversion (holding losers too long)

Loss aversion is when the pain of losing is felt much more strongly than the pleasure of winning (profits).

Loss aversion is one of the big ones in the behavioural finance literature and was developed by Kahneman and his research partner Amos Tversky.

Loss aversion proposes that people’s attitudes towards investment gains and losses are not necessarily symmetrical (i.e., uneven). That is, when an investor loses 30%, the pain and frustration is felt more acutely than the excitement and pleasure they would have felt from making a 30% profit.

The loss aversion bias gives us a rule of thumb: psychologically, the possibility of a loss is on average twice as powerful a motivator as the possibility of making a gain of equal magnitude.

But each person’s loss aversion can differ. One investor may be willing to suffer a 20% loss for a 30% gain, while another investor may be more sensitive to losses and require the possibility of a 50% gain to compensate for the risk of being hit with a 20% loss.

Practically, loss aversion can mean investors are unwilling to sell unprofitable investments. Even if they do not see any prospect for a turnaround, they wait to ‘get even’ on the position before selling.

Similarly, loss aversion can mean investors take profits too early. They are too quick to cut and run on investments that have made a profit. This limits the upside for investors, and can lead to too much trading, which has been showing to limit returns for everyday investors.

Solution:

Day to day, sharemarket’s have only a slightly better than 50% chance of going up and a slightly less than 50% chance of going down. But over longer periods like a month or a year, the odds significantly fall below 50% that your share portfolio will have gone down.

If you’re suffering from loss aversion, look at your portfolio of shares less often. The longer you wait to review your portfolio, the less likely you will be to see a loss and be tempted to sell.

Mental Accounting (not treating all money as equal)

Mental accounting is when we put our money in different buckets which can distort our behaviour.

This bias is a child of Richard Thaler. (For those of you who do not know Thaler he also won the Nobel Prize for Economics in 2017. In the 2015 smash hit The Big Short, Thaler was the character explaining synthetic CDO’s at the blackjack table alongside international pop star Selena Gomez. He is also the author of the wonderful book Nudge.)

With mental accounting, instead of viewing your assets as a single portfolio, your divide your investments into different ‘mental accounts’.

For example, an investor might have put $20,000 into a fund two years ago that has since generated a $10,000 gain. The theory of mental accounting suggests that many investors may be willing to take greater risk with the $10,000 gain portion than they would with the original $20,000.

But a dollar is a dollar is a dollar. That is to say, money is ’fungible’: it is all the same no matter where it came from or how you earned it.

Taking greater risk with the portion gained by treating it as ‘house money’ violates the fact that all money is interchangeable.

Outside of investing, but within personal finance, mental accounting can lead to simple errors like having $10,000 cash in a savings account for a holiday, but having $10,000 of credit card debt. It obviously makes sense to use the holiday funds to pay off the credit card and stop paying huge interest, but the person views the two as separate buckets.

Another version of this is bucketing money and investments according to whether they generate income or capital returns. Total returns are what investors should be focussed on instead. An obsessive focus on income or capital returns can often mean investors have a suboptimal allocation to investments within their portfolio. Remember – capital returns can be used to fund lifestyle expenses too, providing it is sustainable.

Solution: A simple reminder that a dollar equals a dollar no matter which mental account you have it sitting in, can be incredibly valuable. The danger with the “house money” effect on an aggregate level is that it can lead to share market bubbles where investors increasingly take more risks with the newly ‘won’ money.

Confirmation Bias (only seeing what you want to see)

Almost all of us have been guilt of this one at some point in time. It relates to only seeking out or having selective perception for information that confirms our beliefs or values, whilst devaluing those that don’t.

This one stems from the fact that it’s easier to digest information that accords with how we already view the world. The cognitive load is much higher when we have to try and integrate new contradictory information into our worldview.

In investing, this often means ignoring any information that goes against a buy or sell decision we have made in the past, rather than objectively analysing it on its merits. At its worst, it means only constructing an “echo chamber” of information sources so that you never run into a view or data that is going to contradict prior beliefs. The internet has made this echo chamber all the more likely over time as algorithms often selectively find and present you similar content over time – reinforcing previous views.

Solution: Again recognising our tendency for seeking out confirming information is the first step. At Ophir, we actively ask how we could be wrong in our views and seek out people or broker analysts that hold differing views to ours. Someone having a differing view does not necessarily mean you are wrong, but it can help stress test your position to hopefully provide a more balanced view. It also helps to have a wide range of information sources from places such as the internet, podcasts, books, magazines, journals etc that are not just of one ideological bent – lest you only see the world from one narrow perspective.

Slave to vices

Although progress has been significant, there is still much further to go before traditional finance can be integrated with the more dynamic findings from behavioural finance. What is clear is that all investors can benefit from the insights of behavioural finance to understand their own behaviour and preferences better.

As psychologists will tell you, the first step in dealing with an issue, such as these biases, is to recognise there is an issue. There are many great books, such as those listed above, as well as Misbehaving (by Richard Thaler) and Irrational Exuberance (by Rober Shiller) on behavioural finance, and investors could do far worse than reading them to understand more about themselves, and the other investors they are trading with.

At Ophir, we are consciously aware of these four biases in our own investing. But we also see it as an opportunity. We believe the biases lead to investors overreacting and making mistakes that lead to the mispricing of securities.

Astute portfolio managers who appreciate behavioural elements can take advantage of these inefficiencies and opportunities in the market. But without understanding them, investors may continue to be slaves to their own vices.