In our Investment Strategy Note this month we tackle the Russia-Ukraine war, which renowned journalist John Authers recently called (within Europe) “the greatest negative shock to the international order since the end of the Second World War”.

The song ‘War (What is it good for)’ made its singer Edwin Starr a household name in 1970 when it went to no.1 on the Billboard charts. He was not, however, the first to record the hit single and anti-Vietnam-war anthem, with Motown Record’s first string act, the Temptations, having cut a more mellow version in 1969.

When Motown decided to release the song as a single, they worried the controversial song could damage the Temptation’s golden boy image. Instead, they opted for their second-string artist Starr. The song became a runaway hit, only giving up the top spot eventually to Diana Ross’s ‘Ain’t No Mountain High Enough’.

Images are again at stake over a war, with countries the world over being asked to place their allegiances with either Russia or the Ukraine. As expected, democratic countries, including the US, UK and Australia, have rightly resoundingly condemned Russia’s invasion. Some, like China and India, at least to date, appear to be striking a delicate balance to try and remain neutral.

For both of us, and the rest of the team at Ophir, our hearts go out to all those in Ukraine affected by this war, including their friends and family scattered throughout the world. We can only hope that this terrible situation is resolved as swiftly as possible.

But despite the tragic humanitarian situation, as investors, we have a duty to analyse what the war means for markets and our Funds. Below we answer 5 questions about how share markets are likely to deal with the war, the flow-on impacts to growth and inflation, and how the Ophir Funds are responding (or not responding) to the conflict.

1. How important is Russia and Ukraine to the global economy?

In short, not very. Whilst they are ranked no. 1 and no. 2 by landmass in Europe, Russia contributes only 1.7% (less than Texas!) and the Ukraine 0.2% of global GDP – a freckle on the face of global output.

European exports to the two countries are just 0.7% of Europe’s GDP, with this figure less than 0.2% for US exports and less than 0.1% for Australian exports. So the direct impact of a Russian economic collapse would be small.

Both Russia and Ukraine are significant commodity exporters, however, and we have seen certain prices of key commodities they export, namely oil & gas and wheat surge higher. This is probably THE important flow-on effect to the global economy from the war which we will revisit shortly.

2. Will the war in Ukraine hurt share markets?

Winston Churchill once said, “The farther back you can look, the farther forward you are likely to see”.

In light of that, we thought it worthwhile to review how geopolitical events and war have impacted share markets in the past.

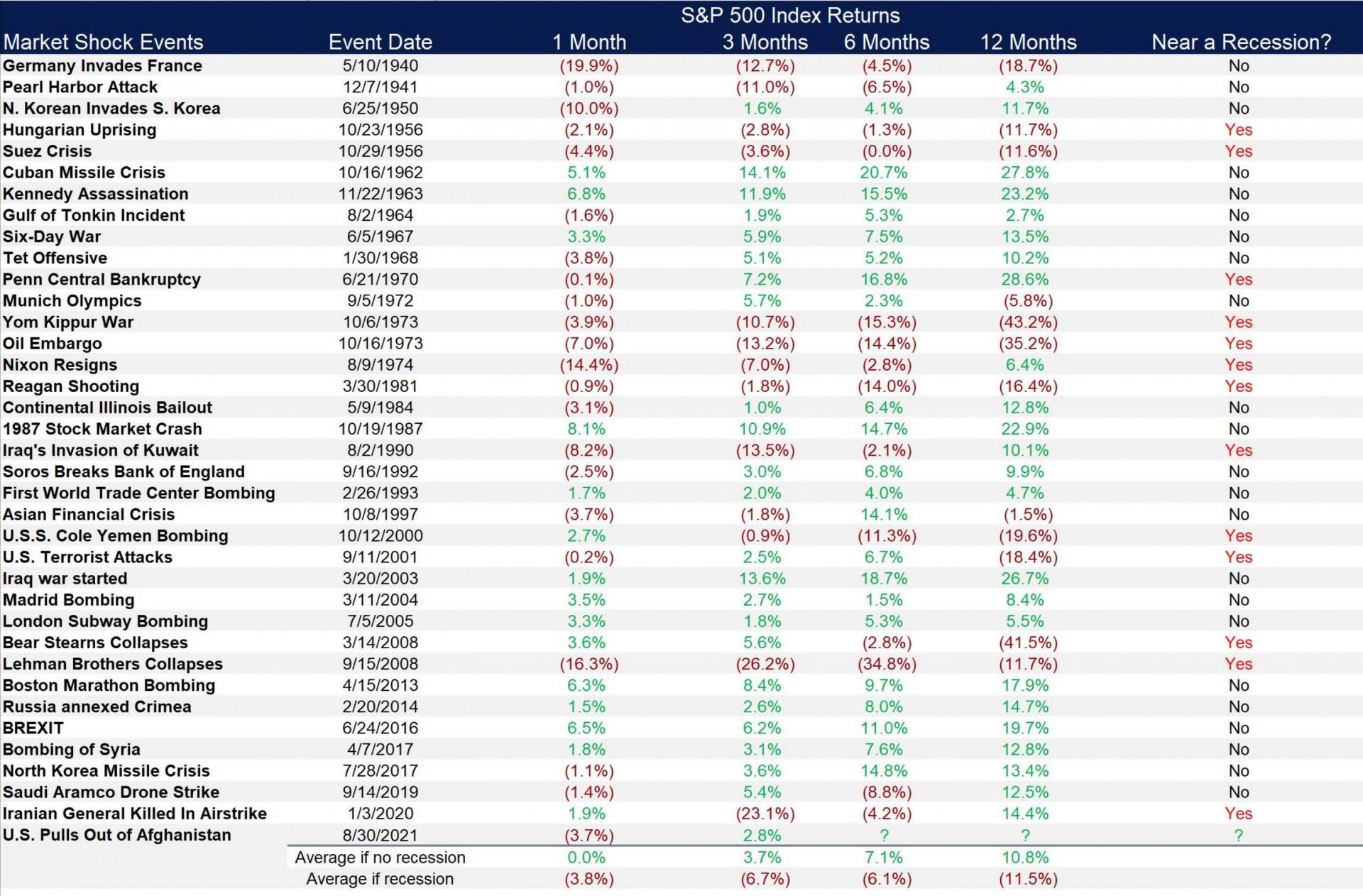

Below is a table of the last 37 major geopolitical events, including wars, from WWII onwards.

Source: LPL Research, S&P Dow Jones Indices

How do stocks do after major events?

The evidence is that, absent a recession, when a geopolitical event strikes, the US market (the world’s major share market which makes up over 50% of the global market) falls initially, but then tends to be materially higher over the next 6-12 months.

Assuming we don’t have a ‘black swan’ event, or the unlikely case of the current conflict escalating into a global war, the consensus remains that we will see above-trend global growth (with no recession) this year. This suggests that we will likely see any share price weakness across our portfolio companies as a buying opportunity. Notably the probability though of a European recession has increased given its reliance on Russian oil and gas (discussed below).

For the Doomsayers out there, it is worth pausing for a moment and looking at what happened during the attack on Pearl Harbour. The S&P500 fell -19.8% top to bottom over a 143-day period and had recouped all its losses in 307 days. A swift recovery for an event much worse than the current war.

What can we glean from this trend from the table of a short, sharp but quite limited fall followed by a swift recovery? Ultimately, economic growth, and more specifically corporate profits (which are what drives share markets), tend to be little affected on a global scale by war, and often benefit from government fiscal (often through increased military spending) and monetary stimulus.

3. What does the war mean for commodity prices?

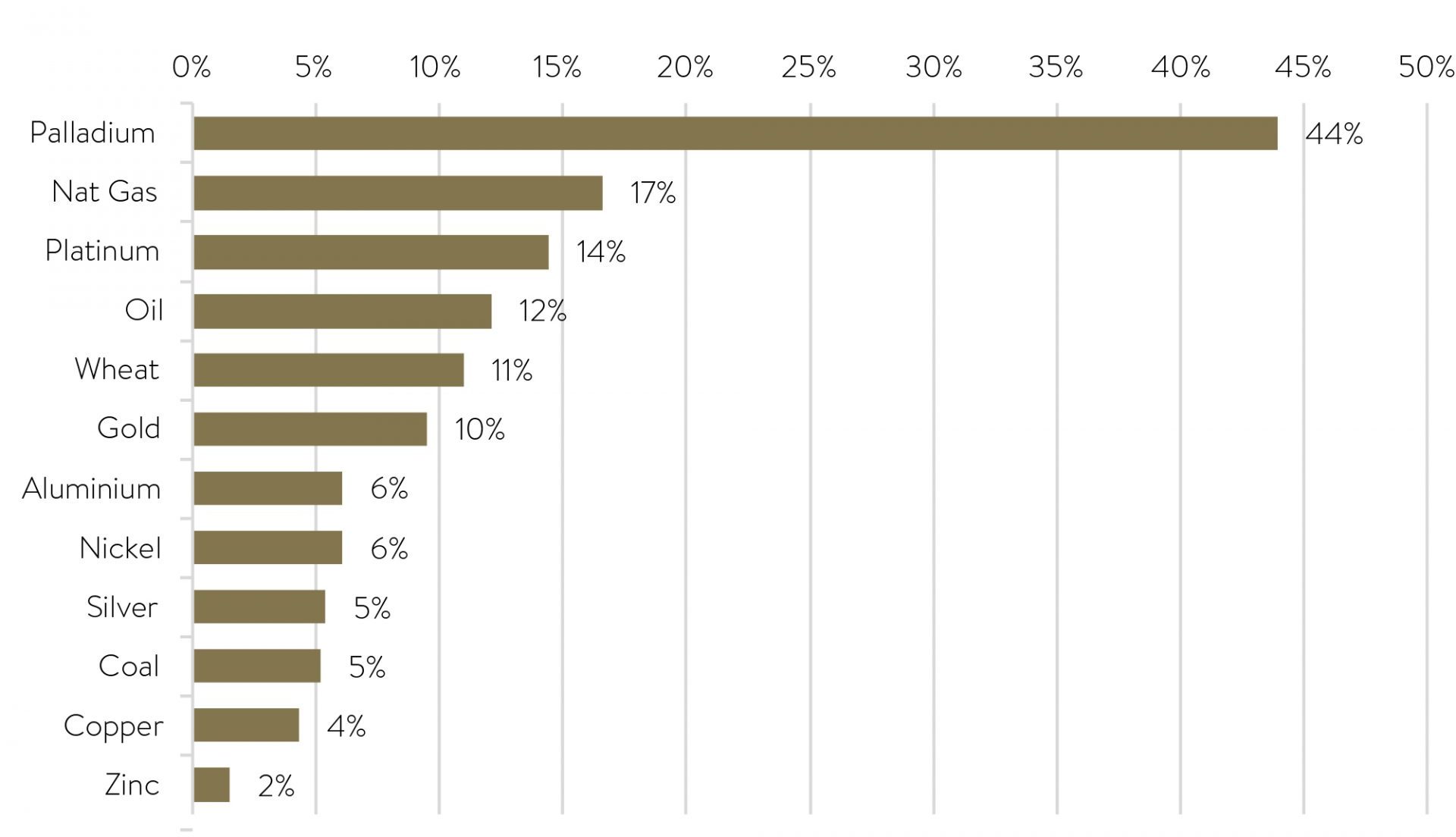

While Russia is a bit player economically these days and a far cry from its former heavyweight status, it is still a significant global commodity exporter, particularly to Europe (see chart below).

Russia share in global commodity production (2020)

Source: J.P. Morgan Commodities Research

Russia is currently the world’s largest exporter of natural gas and the second-largest exporter of crude oil. Importantly, Europe imports 44% of its natural gas and 26% of its oil from Russia.

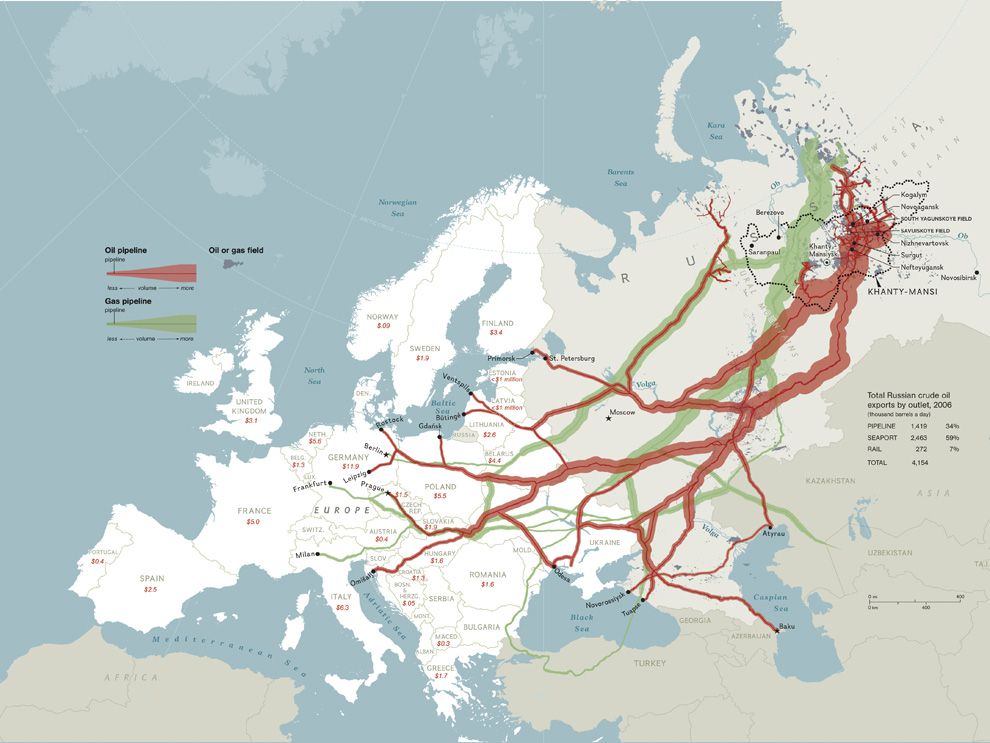

As you can see in the chart below, Russia’s oil and gas pipeline tentacles spread far and wide into Europe, often running through Ukraine.

Source: Nationalgeographic.org

With about a third of Russian government revenue coming from the energy sector though and the West’s reliance on these exports, this mutually beneficial trade has meant that despite the sanctions and backlash against Russia, the West has avoided putting sanctions on energy (though this remains a risk).

But markets still seem to be putting a risk premium on oil and gas, which is likely behind recent price rises. The worry is that higher prices could lead to households spending less and companies earning lower profit margins.

Perhaps the biggest worry, however, is this fuels already high inflation globally. By Goldman Sachs’ numbers, a $10 increase in oil lifts US headline inflation by 0.2% and lowers gross domestic product growth by just under 0.1%.

This is why that word ‘stagflation’ (higher inflation with stagnant economic growth) has started to rear its head again. As seen in the 1970s oil crisis, stagflaton can create a complicated picture for central banks whose tools to fight inflation are best suited when economic growth is also strong.

4. Will central banks hold off raising rates?

The lesson from history is that financial events tend to have much bigger impacts on markets than geopolitical events. Therefore, we think investors should be more concerned with what is going on at the US Federal Reserve Bank currently than what is happening in Eastern Europe. Though, of course, the two are linked to a degree.

With inflation at 40-year highs in the US, the Fed is about to start its interest rate hiking cycle this month. The biggest risk emanating from the war is that higher inflation becomes entrenched, making it more difficult for the Fed to get it under control.

Some may remember Fed chair Paul Volker dramatically raising interest rates to around 20% in the early 1980s to crush spiking inflation, a move the history books widely praise, despite the ensuing recession.

Current chair Jerome Powell knows this history lesson and his eyes remain firmly fixed on inflation and getting on with the job of raising rates this year.

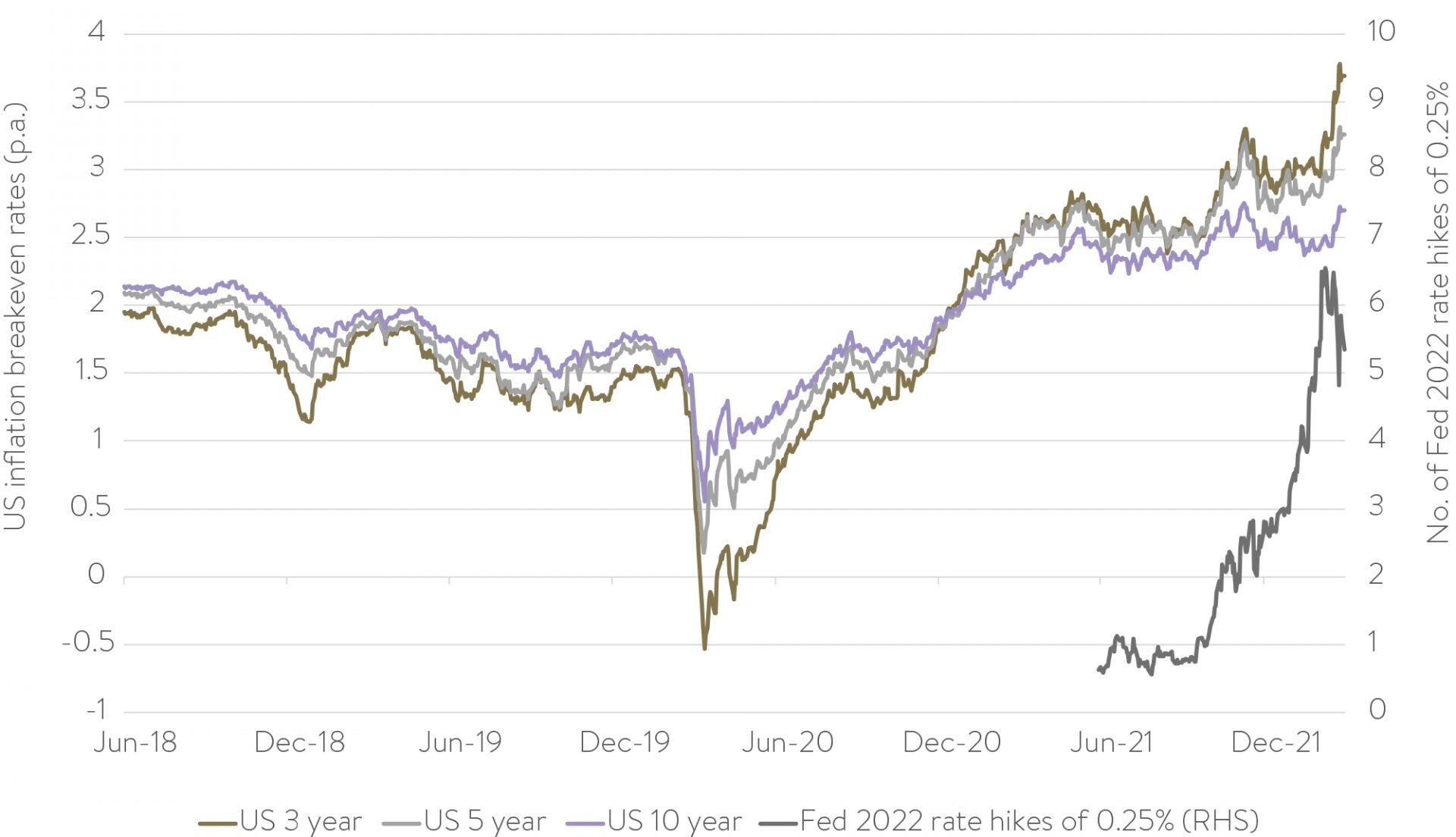

What will have him somewhat worried, though, is the recent jump in market implied inflation over the next few years stemming from the war. We can see this below, with financial markets (via breakeven inflation rates) dramatically lifting expectations for inflation, particularly over the next three years (gold line).

US inflation breakeven rates and Fed rate hikes

With its inflation target at 2%, the Fed will want to make sure the longer-term market views of inflation, such as over the next 10 years (purple line), doesn’t move too far away from the level.

Over the last six months, financial markets have consistently been moving up their expectations for the number of 0.25% Fed rate hikes in 2022 (dark grey line), with almost seven hikes (1.75% total) expected just prior to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Interestingly, that was dialed back to a little less than five hikes (1.25%) when the war broke out because investors believed the uncertainty was more likely to see the Fed ease its foot off the monetary break. In recent days, though, Powell has made it clear inflation is still front and centre in his mind and expectations have risen back to near six hikes (1.50%) this year.

There is no doubt the war is a major source of uncertainty for the Fed. But while it may add a little more caution into rate increases this year, absent a material escalation from Russia or the West, we expect Mr Powell to get on with the job of normalising interest rates this year.

5. How are Ophir’s Funds responding to the war?

First off, it is worth noting that we have no direct exposure in the Ophir Funds to any Russian equities. The Russian sharemarket is classified as an Emerging Market and our global equities exposure is limited to Developed Markets. We do have the flexibility to invest a small portion of our funds in Emerging Markets, but it is not an option we have taken advantage of to date. Any indirect exposure – for example through company revenues linked to the Russian economy – is immaterial.

The most likely scenario is the conflict in Ukraine will remain localised and therefore global sharemarket falls should be limited, with any weakness seen in our portfolio companies as a result likely to be a buying opportunity as highlighted from the historical analysis above.

However, if oil and gas are materially cut off from Russia, or NATO countries become more involved, then we could see further share market falls from here. We hope, and expect, this won’t be the case – but it can’t be ruled out.

It is important to also acknowledge that the Ophir Funds typically have quite limited to no direct exposure to the Energy sector, so we don’t expect absolute returns to be hostage to the vagaries of the impact of the war on commodity prices.

We can expect our Fund’s performance relative to benchmarks to be more volatile given large swings in commodity prices in such an uncertain environment. We are happy to ride this more volatile relative performance given we generally don’t believe we have an edge compared to the market on its pricing of key commodities.

Markets have been rotating away from growth-orientated companies to more value-orientated companies, but in the last week or two, we have seen this pause after longer-term bond yields and the market expectations of the Fed’s interest rate hikes this year – major factors causing the rotation — fell in response to the war.

We think this is more likely to be a pause than an enduring shift back to markets favouring growth.

It is important to point out that small-cap growth companies (our area of focus) have already had their valuations compress a tremendous amount (as covered in our last Letter to Investors), so we think there is less risk of further falls when the pause button is released.

Ultimately, we think investors will become less focussed on the performance of value versus growth companies as their correlations with bond yields is likely to breakdown somewhat when bond yields and valuations of large cap growth companies continue to normalise throughout 2022.